For me it is natural to think that artists reporting on an inner voice are given the choice of listening to this voice or ignoring it. If the artist chooses to listen to this voice, he or she is then required to listen to something that is inside and not outside, since that voice is argued to come from within. The artist must exert a sense of silence that allows listening, i.e. drawing oneself’s attention inward. The act of listening is by definition characterised with an inwards drawing, an absorption of sounds from without and to within. Yet, in the case of an inner voice, artists cannot absorb an external voice, but rather have to absorb an internal one. This could be said to be a form of listening where the artist’s ‘inner ears’ listen to a voice that comes from what I shall call a ‘deeper within,’ a place of silence and stillness.

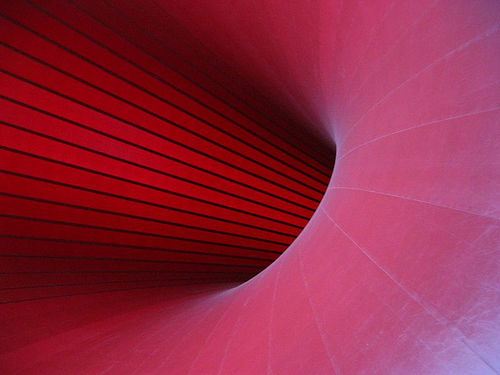

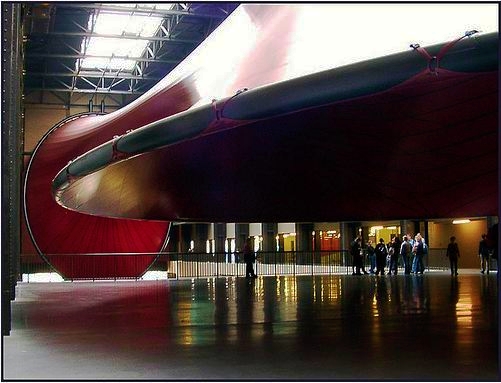

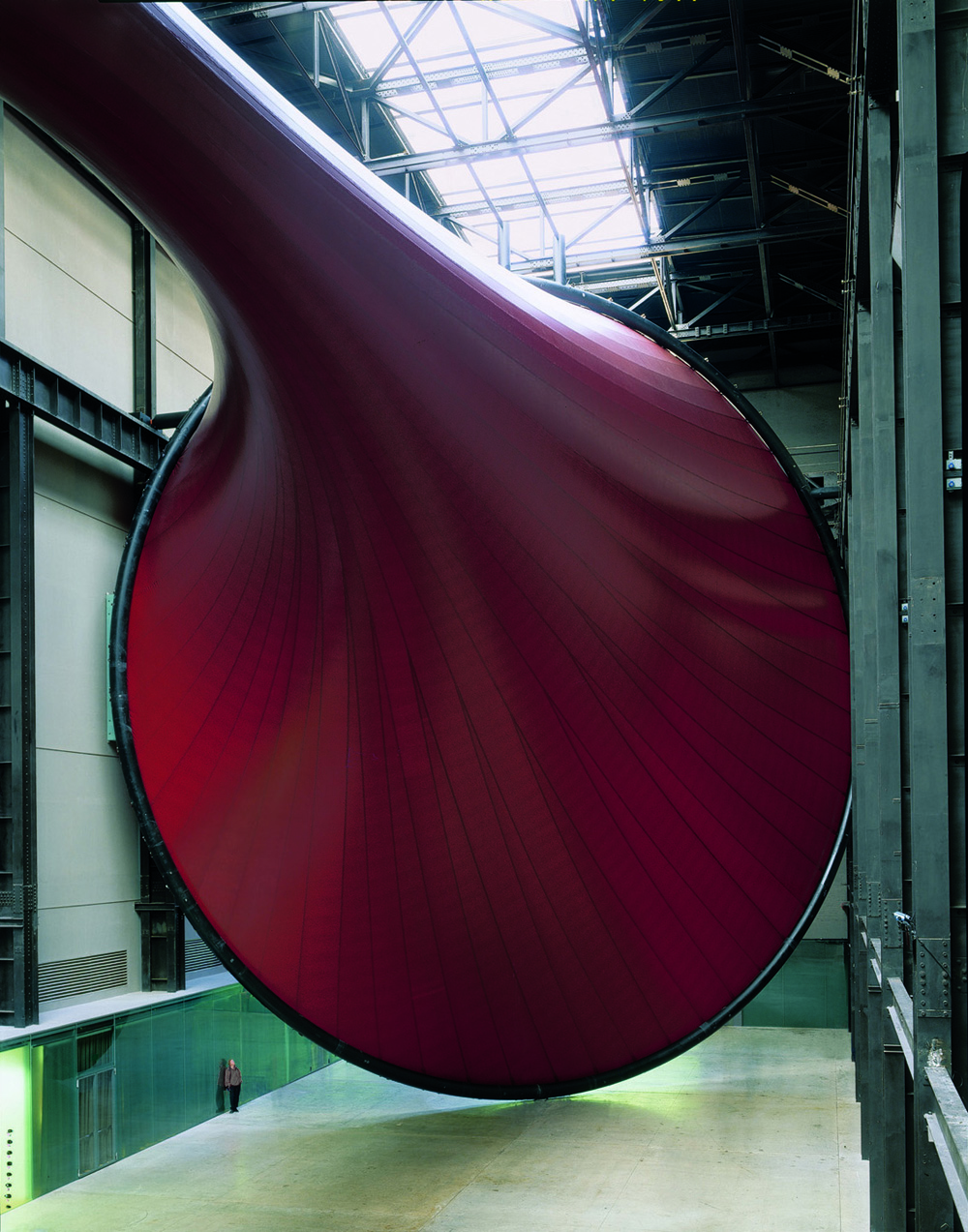

Artist Anish Kapoor (Richards, 2004: 215) describes his momentous works as representing the space within us. Kapoor’s installation work Marsyas (2002; figs. 96-99) at Tate Modern tries to occupy the large space by connecting the space’s three parts with a large PVC membrane tube. The work is described as an exploration of ‘metaphysical polarities: presence and absence, being and non-being…’ (Tate Gallery, The Unilever Series: Anish Kapoor). Following this description I see the work as a symbolic large-scale momentum exploring the duality of sound and silence, with its unique shape resembling large horns or speakers which multiply sounds, as well as large ears which absorb sounds.

Figure 96: Anish Kapoor, Marsyas (2002, PVC and steel installation.) Installation view: Tate, London, 2002-2003. Photo by Flickr’s nahtanoj. Permission to use image obtained from the photographer and Tate Filming Manager, Chris Webster.

Figure 97: Anish Kapoor, Marsyas (2002, PVC and steel installation.) Installation view: Tate, London, 2002-2003. Photo by Norman Craig (Flickr normko). Permission to use image obtained from the photographer and Tate Filming Manager, Chris Webster.

Figure 98: Anish Kapoor, Marsyas (2002, PVC and steel installation.) Installation view: Tate, London, 2002-2003. Photo by Flickr’s nahtanoj. Permission to use image obtained from the photographer and Tate Filming Manager, Chris Webster.

Figure 99: Anish Kapoor, Marsyas (2002, PVC and steel installation.) Installation view: Tate, London, 2002-2003. Photo: John Riddy. Courtesy: Tate. Image supplied by Anish Kapoor Studio. Permission to use image obtained from Anish Kapoor Studio via Lisson Gallery.

Large scale artefacts tend to amaze the viewer due to their size. The image that comes to my mind is of viewers standing at the bottom of this sculpture, raising their heads in silence and in amazement, trying to absorb the grandeur of the sculpture. The vacant area of the Tate gallery’s previous Turbine Hall provides a space where sounds or silence will be multiplied. This can be seen symbolically as representing schools’ national ceremonies or otherwise religious atonement ceremonies where horns are blown, producing loud sounds that stir great awe in the hearts of the spectators. Feelings of awe can be seen for their characteristic element of silence – one keeps silent by standing still and absorbing the loud sound of the horn. Kapoor’s work manages, once again, to deal with metaphysical dualities of sound and silence, where the two are inseparable.

William Blake discusses moments of silence not in the experience of the viewer but rather in the experience of making art. Blake is quoted by Geoffrey Hartman (lecture at The British Academy, London, 3rd October 2007) as saying that he ‘speak[s] silence with my glimmering eyes’. According to Hartman, poets must preserve the belief that all voices are in nature, and are coming ‘out of the silence’. Voices may indicate a form of communication with the artist, or at least a mode where information is transferred through sound and can be received by the artist. This form of communication is expressed by the portraits paintings of Melanie Chan. Chan (![]()

![]() para. 14) asserts that she ‘prefer[s] to be quiet when painting; it is in the silence… that the communion with the flowers can take place’. For Chan the silence is an artistic tool to open up to inspiration, as well as a tool to facilitate a communion with her subject, in what she describes as ‘non-verbal communication’ (para. 28).

para. 14) asserts that she ‘prefer[s] to be quiet when painting; it is in the silence… that the communion with the flowers can take place’. For Chan the silence is an artistic tool to open up to inspiration, as well as a tool to facilitate a communion with her subject, in what she describes as ‘non-verbal communication’ (para. 28).